(an extract from Susannah Clapp’s A Card From Angela Carter, published, excerpted in The Guardian)

Twenty years ago I went for the first time into Angela Carter’s study. I knew the rest of her house in Clapham quite well. Downstairs was carnival: true, there was a serious kitchen, but there were also violet and marigold walls, and scarlet paintwork. A kite hung from the ceiling of the sitting room, the shelves supported menageries of wooden animals, books were piled on chairs. Birds – one of them looking like a ginger wig and called Carrot Top – were released from their cages to whirl through the air, balefully watched through the window by the household’s salivating cats. “Free range,” said Angela. Here Angela’s husband Mark Pearce dreamed up the pursuits he went on to master: pottery, archery, kite-making, gunmanship, school-teaching; here friends streamed in and out for suppers; here their son, Alexander, was a much-hugged child.

The study was unadorned, muted, more 50s than 60s. Not so much carnival as cranial. There was a small wooden desk by the window looking down to the street, The Chase: “SW4 0NR. It’s very easy to remember. SW4. Oliver. North. Reagan.” There was a grey filing cabinet, shabby, well organised and stuffed with papers. I knew some of what I would find in that cabinet – Angela had told me.

She had died a few weeks earlier, on 16 February 1992. She was 51 and had been suffering from lung cancer for over a year. Her early death sent her reputation soaring. Her name flew high, like the trapeze-artist heroine of Nights at the Circus: Fevvers, the “Cockney Venus”. Three days after she died, Virago sold out of Angela’s books. She became, in words from the two poles of her vocabulary, an aerialiste and a celeb.

Not that her fiction and her prose went unacknowledged while she was alive. She was not neglected and rarely had anything rejected; she was given solo reviews and launch parties; she went on television; she got cornered by fans. But she was not acclaimed in the way that the number of obituaries might suggest. She was 10 years too old and entirely too female to be mentioned routinely alongside Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and Ian McEwan as being a young pillar of British fiction. She was 20 years too young to belong to what she considered the “alternative pantheon” of Iris Murdoch, Doris Lessing and Muriel Spark in the 40s.

We had talked about these things a year earlier, after her illness had been diagnosed and she had asked me to be her literary executor. We had met at the end of the 70s, when I was helping to set up the London Review of Books and was keen to get Angela to write for the paper. Liz Calder, who had published The Passion of New Eve and The Bloody Chamber at Gollancz, arranged an introduction and, swaddled in a big coat, Angela came into the small office, which had been carved out of the packing department in Dillons bookshop. She lit up the paper’s pages for the next 12 years. And we became friends.

Her requirements for her estate were relaxed, if not exactly straightforward: I should do whatever was necessary to “make money for my boys”, for Mark and Alexander. There was to be no holding back on grounds of good taste; she had no objections to her prose being turned into an extravaganza on ice: on the contrary. Her only stipulation was that Michael Winner should not get his hands on it.

I, of course, hoped to find in that filing cabinet a fragment from an abandoned novel or a clutch of unhatched short stories. And of course I knew I would not. For all her wild hair, Angela was careful. She was, as she put it, “both concentrated and random”. In the depths of her illness she had drawn up a plan for a final book of short stories, writing down the number of words alongside each title, and hoping that “all together, these might make a slim, combined volume to be called ‘American Ghosts and Old World Wonders'”: they did. In one of her desk drawers there was a small red cashbook in which she wrote down her fees and expenses. No big fiction had been left unpublished. But there were surprises. I knew she had drawn but I had not realised how much. Tucked in among the files were richly coloured crayon pictures: of flowers with great tongue-like petals, of slinking cats, and of Alexander, whose baby face with its bugle cheeks, dark curls and big black eyes looked like that of the West Wind on ancient maps; his mother described his face as being like a pearl.

She had told me that she kept journals and described the shape they took. They were partly working notes and partly casual jottings, roughly arranged so that the two kinds of entry were on opposite pages. They were stacked in the study: lined exercise books in which she had started to write during the 60s and which covered nearly 30 years of her life. She decorated their covers as girls used to decorate their school books, with cut-out labels (the Player’s cigarette sailor was one), paintings of cherubs and flowers and patterns of leaves.

Inside she described, in her clear, upright, not quite flowing hand “a smoked gold day” in 1966, and in the same year made a list of different kinds of monkeys: rhesus, capuchin and lion-tailed. She wrote of the “silver gilt light on Brandon Hill” in 1969, jotted down a recipe for soup using the balls of a cock and, in her later pages, took notes on Ellen Terry’s lectures on Shakespeare. She made, again and again, lists of books and lists of films (Jean-Luc Godard featured frequently). She did not write down gossip (though she liked gossip), and wrote little about her friends. She specialised in lyrical natural description and in dark anecdote. She noted that the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe had died of a burst bladder because he had not dared to get up from a banquet to have a pee. She observed that the pork pies favoured by her mother’s family for wakes “possess a semiotic connection with the corpse in the coffin – the meat in the pastry”, and added, referring to Beatrix Potter’s most chilling tale of fluffy life: “Tell that to Tom Kitten.” She wondered what smell Alexander would remember from his childhood home.

The revelation for me in the journals was that, in her 20s, Angela had written poems – verses that strikingly prefigured her novels in richness of expression, in their salty relish, in their feminism and in their use of fable. At the same time she produced a statement of intent which came startlingly close to prophesy: “I want to make images that are personal, sensuous, tender and funny… I may not be very good yet but I’m young and I work very hard – or fairly hard.”

I have a small collection of Angela material. As well as the newspaper cuttings, the business notes from publishers, the grief-filled letters from friends after her death, there are a few browning, frayed letters, written mostly on lined exercise-book paper, always in longhand (though her hand was square rather than long). There is on my mantelpiece a clockwork Russian doll, made out of tin with bright orange blotches on her cheeks and a design of blue teardrops on her stiff full skirt: a present from Angela and Mark. And there are a dozen or so cards, dashed off in greeting or explanation, sometimes with a full message, sometimes just a salute. These cards make a paper trail, a zigzag path through the 80s. They are casually dispatched – some messages are barely more than a signature – but are often the more telling for that: they catch Angela on the wing, shooting her mouth off. She would have hated the idea of a soundbite, but she had a gift for a capsule phrase, for a story in a word. In their celerity, postcards are the email of the 20th century, but they are also more than that. They tell more than one story: the photographs, paintings and cartoons that Angela chose sometimes reinforce but often contradict the message on the other side. They can contain hidden histories: some of Angela’s images glance back at an episode in her life, or hint at a conversation we had been having. Sometimes, of course, the choice of picture is random: it hints at nothing. In a few years’ time it will be harder to know which is random, which is allusive.

I first looked at these cards when writing a series of talks about postcards for Radio 3; I looked at them again when it was suggested to me that those talks might become a book. I look at them now with the idea that they evoke some of the occasions, preoccupations and delights of Angela’s life. A life of which, as she put it, “The fin has come a little early this siècle.”

Living dolls

Here they are, the girls. Five of them sitting in a row. Some are smaller in girth than others, but all of them have plump curved cheeks, dark almond eyes and slightly open cupid mouths. Each is decorously clad in early 20th-century mode. But their stiff legs are wide apart, their long skirts are partly rolled up; you can see petticoats and a flash of drawers.

The card, posted in the summer of 1989 from London but bought in Hungary, was nearly not sent. Angela’s blue-biro message says: “Budapest is bliss, bliss, bliss. So much so that I never got to post any letters.” She has added in black ink: “I found this among my souvenirs & thought I’d post it off, anyway.” I’m glad she did. Of the cards I’ve seen from Angela, certainly of those she sent me, this brown and white, lush but shadowy photograph is the one that most evokes her stories and essays: not her style – the picture is posed, stately, static, striving for correctness, the very opposite of Angela’s helter-skelter hoopla prose – but her subject matter. These creatures are dolls – it’s hard not to think of The Magic Toyshop – whose bodies are too rigid to be saucy and too adult to be petted; they are showcases of femininity, made-up versions of the sex that makes itself up.

By the time I knew her, Angela’s face was free of make-up and her hair stripped of dye. She was the first woman I knew who went grey without looking like a granny. Her disregard not only for fashion but for neatness was a dirty-strike display. It was not that she was uninterested in people’s appearance – on one of the last afternoons I spent with her she went through our acquaintances ranking them in order of handsomeness. Still, she herself stopped putting on the Ritz. Antonia Fraser, appearing on a television programme with Angela, once said that she had not been able to conceal a flicker of astonishment when Angela had admired her dress. No flicker was ever lost on Angela. “I wonder why people are always so surprised when I’m interested in clothes,” she said, not wondering at all. And laughed.

Angela laughed often and loudly. She was a cackler. She was also a talker, a gasser and a tremendous chatterer on the phone. She knew what it was to make a voice distinctive – as a schoolgirl she had wanted to act – and her own tones were unmistakable.

Piping, soft, with clipped vowels, at times Angela sounded like a parody of girlish gentility. At other times she skidded into casual south London. You never knew exactly where you were. She was impossible to second-guess. She was a great curser, and took pride in this: “I am known in my circle as notoriously foul-mouthed.” Yet she was also byzantinely courteous: her most full-blooded protests would often be heralded by an icily disarming “forgive me”.

Geisha

Geisha Boop arrived in my flat on a card in vivid Technicolor. The card, evidently sent in an envelope, is undated but must have been dispatched in the late 80s. The message reads: “That was a really terrific party on Monday. I was glad I went. But – why has Marianne gone blonde?!?” It is the reference to Marianne Wiggins that dates the card. The picture itself carries a memory of an earlier time: of Angela’s first big excursion and her escape from England.

In 1969, when she had published three novels and been married to Paul Carter for some eight years, she won the Somerset Maugham award for Several Perceptions. The award, given to a writer under 35, was to be used for travel. Angela fulfilled that requirement, but gave it a twist: “I used the money to run away from my husband, actually. I’m sure Somerset Maugham would have been very pleased.”

She ran to Japan, the only country that met her stringent criteria for a bolthole: she wanted to live in a non-Judaeo-Christian culture, but it had to be a culture with a good sewage and transport system. She had gone off with a Japanese man, a “very good-looking bastard… just what I needed after nine years of marriage”, and it changed her. “I became a feminist when I realised I could have been having all this instead of being married.”

In Japan she became enthusiastic about sex. She found even the ads for the VD clinics jolly: “Let me,” they cajoled, “cure your chronic gonorrhoea.”

Bard

In 1988, four years before she died, Angela sent a Bard card from the Stratford Ontario Shakespeare festival, in Canada. In fluorescent yellow, neo-Renaissance Palatine italics and an exclamation mark, it proclaims: “So I haven’t written much lately! So what? Neither has Shakespeare.”

The message on the back reports only that “Canada’s nice. Especially Montreal. Like Scandinavia with liquor.” At the time she sent this card, Angela was dreaming up Wise Children, her last novel, and her Shakespeare book, a buoyant wise-cracker about hoofing and singing twins. She had set out intending to make in it some reference to all of Shakespeare’s plays: only a few eluded her.

The card may have been offering a semi-apology for a refusal to write something for the London Review; my attempts to coax her on to the page quite often met with refusals. She may have been wincing about the late delivery of a piece of copy. She liked the idea that journalism ran through her veins and was a terrific deadline surfer: “the only time I ever iron the sheets or make meringues is when there is an absolutely urgent deadline in the offing”.

Still, in this Shakespeare card she was most likely nodding to the four years that had passed since the publication of Nights at the Circus. There was a good reason for the gap between Angela’s books. In 1983 she had become pregnant. She was 42, mature for a first-time mother, and she was thrilled and alarmed: “Alex came as a great surprise to us,” she told me. Her pregnancy was not calm. She was not altogether well, and she did not take things easy. One of her tasks was the judging of the Booker prize. It was the year that Fay Weldon presided over an unusually female-strong panel (Angela and Libby Purves sat in judgment alongside the literary editor Terence Kilmartin and the poet Peter Porter), and must have been an unsettling experience for Angela, whose own work had never been selected by a panel of judges.

It was to become even more unsettling. After the dinner at which the announcement of the winner (JM Coetzee’s Life and Times of Michael K) had been made, the television presenter Selina Scott went around with her mic, smiling and making mistakes. She went up to Angela and apparently mistook her for one of the many hangers-on at the feast, inquiring what she thought of the judges’ decision. “I’m one of the judges,” Angela explained, leaning away from her interrogator with a grimly polite chuckle. “Does that exclude me…?” Poor Scott seemed mystified: “I’m sorry… What’s your name?”

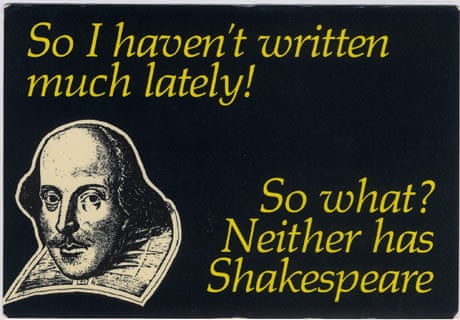

Chili

In 1985 she sent me a postcard from Austin, Texas. The picture showed a black cauldron bubbling with beans and frighteningly red beef, sending off a swirl of blue smoke; alongside it lay peppers, an open bottle of Lone Star beer – and a recipe for Texas Chili. Angela’s message runs: “Carter’s reply to her critics! Texas chili, it goes through you like a dose of salts. I would like to forcefeed it to that drivelling wimp… preferably through his back passage. (I do think all that fuss was comic, though). Temperatures in the ’80s. Everybody is loony, here.”

At the beginning of the year she had reviewed an assortment of volumes about food – The Official Foodie Handbook, Elizabeth David’s An Omelette and a Glass of Wine and the Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook – for the London Review of Books. In a sustained piece of invective, and a dextrous analysis of manners, she tore into “piggery triumphant… [the] unashamed cult of conspicuous gluttony in the advanced industrialised countries, at just the time when Ethiopia is struck by a widely publicised famine”. It was not only the inequity and the waste that enraged her, it was also what she saw as the snobbery of that newly emerging species, the foodie. “This mincing and finicking obsession with food opens up whole new areas of potential social shame. No wonder the British find it irresistible.” Furious responses – some of them alluding to the pregnancy which had delayed her piece – appeared on the paper’s letters pages: “A woman capable of splashing blame for the Ethiopian famine on Elizabeth David is scarcely to be trusted with a baby’s pusher, let alone a stabbing knife.”

These critics were as wrong in thinking Angela uninterested in food as they were in misreading her to mean that foodies were actually responsible for famine. She did take pride in a certain austerity: she spoke of herself as having been formed by the “mild discomfort” of England in the 40s, and approved of its nourishing plainness, of “the fact that you were always a little bit healthily cold, and yet you had brown bread”. Yet austerity in her was the flipside of relish and gusto.

Angela was fiercely interested in the history of food and in its social implications. The book she had chosen for Desert Island Discs was Larousse Gastronomique: she wanted, she said, to take something that would be “a good read”. Still, her interest was also practical, personal. In the kitchen in Clapham she served up rabbit and broccoli, and lamb and apricots (the last cooked with a cat sitting on her lap). She was not much of a drinker; the first time I went to supper at 107 The Chase, I was dashed to see that as soon as the first glasses of white wine had been poured, the bottle was stoppered up and put back into the fridge. She had, she said, cooked “endlessly, elaborately” during her first marriage, and claimed that, after they split up, her husband had accused her of having produced batches of wonderful cakes “in order to make him fat and unattractive to other women. That was characteristic of my Machiavellian mind.”

Angela herself did not eat cakes. Although she was a generous dolloper-out of food, her eating habits had been, for a large part of her life, irregular and sometimes dangerous. As a young girl she had been large, with a chubby face, and had reached her adult height of more than five foot eight by the time she was 13. At the age of 18 she changed shape as dramatically as a creature in one of the fairy tales that fascinated her. She became anorexic.

She was clear about the reasons for this: she wanted to take control of her life and wrest her future away from her parents. Her father was “fearless and unimaginative”, her mother came from “the examination-passing working classes”. Both parents were possessive though in rather different ways; looking back on her adolescence, Angela thought of herself spending a large part of it entrenched in hostility towards them. Her mother indicated that if her daughter got a place at Oxford, she and her husband would be likely to get a flat or house nearby: “I think that’s when I gave up working for my A levels,” Angela explained. And just after she’d taken her exams (only two of them), she gave up eating.

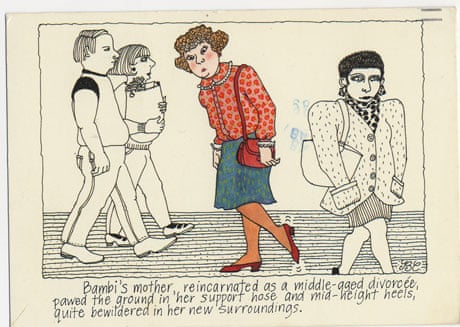

Bambi

“I decided I’d be thin and it all got completely out of hand.” It happened very quickly. She lost about 38 kilos in six months and suddenly looked completely different. She was spindly, with very short curly hair and she did not know whether this extraordinary new appearance was nice or nasty. Sometimes “I looked like Byron”. Often she looked like a model, though even when her shape was tight, her features were luscious. She dressed “like a 30-year-old divorcée”. It was 1958: she got herself up in Chanel-style suits, stilettos and black stockings.

One of her postcards suggests something of this teenage shape-shifting. In the late 1980s Angela sent a droll picture from somewhere near the Erie Canal. It captured her bemusement and her fashion sense, though not the beauty of the young, primly costumed Angela. “I think this is very funny, but I’m not sure why,” runs her message. The caption declares: “Bambi’s mother, reincarnated as a middle-aged divorcée, pawed the ground in her support hose and mid-height heels, quite bewildered in her new surroundings.”

Angela reckoned that as an acute condition her anorexia lasted for about two years, but in its chronic form it went on well into her mature life. Right up to the birth of her son her eating patterns were “still strange”. For some 20 years she levelled out at about 63 kilos but, after Alexander, she steadily put on weight. “But I wasn’t worried any more. I felt so much better when I was fatter. It made me think that inside every thin woman there’s a fat woman trying to get out.”

Ritzy

“Oh,” she said to the artist Corinna Sargood on the phone, soon after the news of her illness had broken, “A man’s coming to the door.” Pause. “It’s all right. I’ll let him in. He hasn’t got a scythe.” In the Brompton hospital a month or so before she died, she worked on the manuscript of The Second Virago Book of Fairy Tales. She had gathered these stories from all over the place – from Norway and Burma and Palestine and Mordvinia – and grouped them under headings which included “Strong Minds and Low Cunning” and “Up to Something – Black Arts and Dirty Tricks”. “I’m just finishing this off for the girls,” she explained, with a nod at the manuscript on her bed.

Back at home, with Mark at the front door warding off people who took it into their heads to drop in, she entertained. I remember her, in October 1991, angry because the Labour Party had rung her on the day she came out of hospital to badger her about a fundraising dinner; she had recently been asked by the Evening Standard why she supported Labour: “Well,” she said, “the Labour Party, it’s like an old sofa, you go on sitting on it even if it is Kinnock-stained.” She was thin, then, and wore a red ribbon wound around her head and tied in a bow.

In the midst of her treatment she concocted a riposte to the Booker, which expressed her comic contempt for much of the fiction flying around the place. Once more missing from the shortlist for the prize, she had, she noted, failed to get the sympathy vote. So she would write a long novel featuring a philosophy don, his mistress and time travelling. It would be called “The Owl of Minerva” – and she knew it would win.

For what turned out to be Salman Rushdie’s last visit, Angela insisted not only on getting up but dressing up, serving tea with an almost Japanese formality, laying out a tea service (perhaps in memory of the rosebud set her mother so cherished) and biscuits. It was one of her gifts to deal in a sort of double irony, to send up a daintiness of manner and yet to honour it at the same time. As she poured, she cursed her illness but took satisfaction from the fact that just before her diagnosis she’d taken out a whopping insurance policy; she “thought it very funny”, Rushdie said, “that the insurance company were screwed”.

The last time I saw her, in January 1992, she was in bed, with light belting in from the windows and the smell of incense, given her by her next-door neighbour, filling the room. We had Tuscan bean soup. She wanted news of parties and literary gossip. She was on steroids and morphine; her face looked rosy and round and smooth. The ribbon in her hair this time was pink, and on the cassette machine at her side she played a tape of Blossom Dearie.

She died on Sunday 16 February. She had had some terrible moments of distress – she told Mark that she had been invaded by aliens – but a large part of her illness had been peaceful, and she had taken command of the organisation of her funeral, leaving precise instructions about who was to be there, what music should be played and what might be read.

On 19 February, at Putney Vale Crematorium, Angela’s brother Hugh played the organ: “Sheep May Safely Graze” at the beginning and ‘”Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” at the end. We sang the 23rd Psalm (“Crimond”). Carmen Callil spoke about her friend. Salman Rushdie read Andrew Marvell’s poem “On a Drop of Dew”. Alexander carried a lily and a red rose to put on his mother’s coffin.

Coming out of the chapel into the hectic luxuriance of the crematorium grounds, it was as if Birnam Wood had come to Putney Vale. The surrounding trees rearranged themselves. They shifted and they sprouted feet. They marched and dispelled, shaking themselves free of foliage. They changed into Special Branch men, who were moving forward to enclose the author of Midnight’s Children, in hiding because of the fatwa imposed on him by the Ayatollah Khomeini three years earlier. The previous year, when Angela was working on the strongly secular television documentary The Holy Family Album, Rushdie had offered her advice on how to deal with blasphemy. “I don’t think,” she had gleefully retorted, “I need any help from you.”

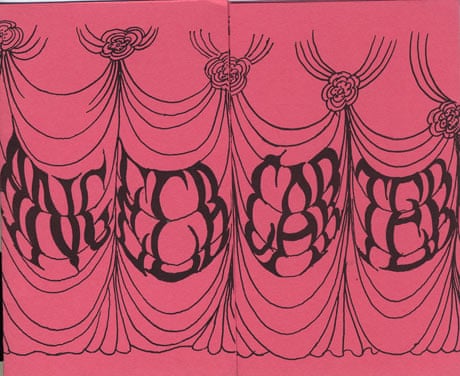

The memorial service, held some five weeks later, was as expansive, inclusive and gaudy as the funeral had been small, plain and sober. Corinna Sargood created a shocking-pink invitation to celebrate Angela’s life and works at the Ritzy cinema in Brixton at 11am on Sunday 29 March. It was Mark who came up with the idea of the Ritzy. It was a homage to Angela’s love of the flicks; the hoofing heroines of her last novel would have felt at home there; it was splendid but battered, and had nothing super or American about it; it was in south London, where she had made her home.

The morning was based on Desert Island Discs. Angela had been asked to go on the programme towards the end of her life: she had chosen her eight records, the book she would take and her luxury, but she was never recorded.

Michael Berkeley, composer, broadcaster and friend, was the compere. He sat on a podium with a cassette machine in front of a folding screen, which Corinna had painted with tropical verdure. He announced the tapes and summoned up the speakers: people from different parts and times of Angela’s life stood in for her voice. Carmen, wearing her koala bear jumper (“for Angie”), spoke, as she had at the funeral. Rebecca Howard talked; so did Caryl Phillips. Tariq Ali fired off about the miners’ strike and made Salman Rushdie cross when he called the Ritzy a fleapit. Lorna Sage arrived just before the morning kicked off: she was pale, slightly stooped and breathless. She, too, was to die in her 50s, but her long blonde hair streamed down as if she were a 19-year-old.

For her records, Angela had chosen Debussy’s “The Girl with the Flaxen Hair”, because Hugh had played it when he was a music student, and Muddy Waters’ “Mannish Boy” because it brought back the 50s. She wanted an extract from Schumann’s Dichterliebe, sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, because it was the first LP she ever bought, and Billie Holiday – her voice shot through with crackles and sighs – singing “Willow Weep”, because it reminded her of Streatham ice rink. She asked for Sviatoslav Richter playing Schubert’s B flat Piano Sonata, which she described as her favourite piece of music; in one of our last meetings she had said she now preferred Schubert to Beethoven – “more heart”. Woody Guthrie’s “Riding in My Car” she chose because she liked being driven and because it reminded her of being in the car with Alexander, who was learning it on his guitar. The penultimate number was Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry” and the final record was one of Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs; Hugh said that was something on which she would never have alighted had she not been ill. In the middle of it, a poster of Wise Children which had been stuck up at one side of the stage came loose and fluttered down.

When the time came for Angela’s luxury to be announced, Mark and Alexander came up from the audience and on to the stage. They turned around Corinna’s bright screen. On the back of the scene of island vegetation she had painted Angela’s choice of luxury. It was a zebra.

Susannah Clapp is the Observer’s theatre critic

A Card From Angela Carter by Susannah Clapp is published by Bloomsbury on 16 February, £10. The book, read by Susannah, will be Radio 4’s Book of the Week from Monday 6 February, 9.45am/12.30am