Brief highlights from an interview of Angela Carter by Lisa Appignanesi.

Apologies for the poor quality of the video.

Brief highlights from an interview of Angela Carter by Lisa Appignanesi.

Apologies for the poor quality of the video.

(an extract from Susannah Clapp’s A Card From Angela Carter, published, excerpted in The Guardian)

Twenty years ago I went for the first time into Angela Carter’s study. I knew the rest of her house in Clapham quite well. Downstairs was carnival: true, there was a serious kitchen, but there were also violet and marigold walls, and scarlet paintwork. A kite hung from the ceiling of the sitting room, the shelves supported menageries of wooden animals, books were piled on chairs. Birds – one of them looking like a ginger wig and called Carrot Top – were released from their cages to whirl through the air, balefully watched through the window by the household’s salivating cats. “Free range,” said Angela. Here Angela’s husband Mark Pearce dreamed up the pursuits he went on to master: pottery, archery, kite-making, gunmanship, school-teaching; here friends streamed in and out for suppers; here their son, Alexander, was a much-hugged child.

The study was unadorned, muted, more 50s than 60s. Not so much carnival as cranial. There was a small wooden desk by the window looking down to the street, The Chase: “SW4 0NR. It’s very easy to remember. SW4. Oliver. North. Reagan.” There was a grey filing cabinet, shabby, well organised and stuffed with papers. I knew some of what I would find in that cabinet – Angela had told me.

She had died a few weeks earlier, on 16 February 1992. She was 51 and had been suffering from lung cancer for over a year. Her early death sent her reputation soaring. Her name flew high, like the trapeze-artist heroine of Nights at the Circus: Fevvers, the “Cockney Venus”. Three days after she died, Virago sold out of Angela’s books. She became, in words from the two poles of her vocabulary, an aerialiste and a celeb.

Not that her fiction and her prose went unacknowledged while she was alive. She was not neglected and rarely had anything rejected; she was given solo reviews and launch parties; she went on television; she got cornered by fans. But she was not acclaimed in the way that the number of obituaries might suggest. She was 10 years too old and entirely too female to be mentioned routinely alongside Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and Ian McEwan as being a young pillar of British fiction. She was 20 years too young to belong to what she considered the “alternative pantheon” of Iris Murdoch, Doris Lessing and Muriel Spark in the 40s.

We had talked about these things a year earlier, after her illness had been diagnosed and she had asked me to be her literary executor. We had met at the end of the 70s, when I was helping to set up the London Review of Books and was keen to get Angela to write for the paper. Liz Calder, who had published The Passion of New Eve and The Bloody Chamber at Gollancz, arranged an introduction and, swaddled in a big coat, Angela came into the small office, which had been carved out of the packing department in Dillons bookshop. She lit up the paper’s pages for the next 12 years. And we became friends.

Her requirements for her estate were relaxed, if not exactly straightforward: I should do whatever was necessary to “make money for my boys”, for Mark and Alexander. There was to be no holding back on grounds of good taste; she had no objections to her prose being turned into an extravaganza on ice: on the contrary. Her only stipulation was that Michael Winner should not get his hands on it.

I, of course, hoped to find in that filing cabinet a fragment from an abandoned novel or a clutch of unhatched short stories. And of course I knew I would not. For all her wild hair, Angela was careful. She was, as she put it, “both concentrated and random”. In the depths of her illness she had drawn up a plan for a final book of short stories, writing down the number of words alongside each title, and hoping that “all together, these might make a slim, combined volume to be called ‘American Ghosts and Old World Wonders'”: they did. In one of her desk drawers there was a small red cashbook in which she wrote down her fees and expenses. No big fiction had been left unpublished. But there were surprises. I knew she had drawn but I had not realised how much. Tucked in among the files were richly coloured crayon pictures: of flowers with great tongue-like petals, of slinking cats, and of Alexander, whose baby face with its bugle cheeks, dark curls and big black eyes looked like that of the West Wind on ancient maps; his mother described his face as being like a pearl.

She had told me that she kept journals and described the shape they took. They were partly working notes and partly casual jottings, roughly arranged so that the two kinds of entry were on opposite pages. They were stacked in the study: lined exercise books in which she had started to write during the 60s and which covered nearly 30 years of her life. She decorated their covers as girls used to decorate their school books, with cut-out labels (the Player’s cigarette sailor was one), paintings of cherubs and flowers and patterns of leaves.

Inside she described, in her clear, upright, not quite flowing hand “a smoked gold day” in 1966, and in the same year made a list of different kinds of monkeys: rhesus, capuchin and lion-tailed. She wrote of the “silver gilt light on Brandon Hill” in 1969, jotted down a recipe for soup using the balls of a cock and, in her later pages, took notes on Ellen Terry’s lectures on Shakespeare. She made, again and again, lists of books and lists of films (Jean-Luc Godard featured frequently). She did not write down gossip (though she liked gossip), and wrote little about her friends. She specialised in lyrical natural description and in dark anecdote. She noted that the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe had died of a burst bladder because he had not dared to get up from a banquet to have a pee. She observed that the pork pies favoured by her mother’s family for wakes “possess a semiotic connection with the corpse in the coffin – the meat in the pastry”, and added, referring to Beatrix Potter’s most chilling tale of fluffy life: “Tell that to Tom Kitten.” She wondered what smell Alexander would remember from his childhood home.

The revelation for me in the journals was that, in her 20s, Angela had written poems – verses that strikingly prefigured her novels in richness of expression, in their salty relish, in their feminism and in their use of fable. At the same time she produced a statement of intent which came startlingly close to prophesy: “I want to make images that are personal, sensuous, tender and funny… I may not be very good yet but I’m young and I work very hard – or fairly hard.”

I have a small collection of Angela material. As well as the newspaper cuttings, the business notes from publishers, the grief-filled letters from friends after her death, there are a few browning, frayed letters, written mostly on lined exercise-book paper, always in longhand (though her hand was square rather than long). There is on my mantelpiece a clockwork Russian doll, made out of tin with bright orange blotches on her cheeks and a design of blue teardrops on her stiff full skirt: a present from Angela and Mark. And there are a dozen or so cards, dashed off in greeting or explanation, sometimes with a full message, sometimes just a salute. These cards make a paper trail, a zigzag path through the 80s. They are casually dispatched – some messages are barely more than a signature – but are often the more telling for that: they catch Angela on the wing, shooting her mouth off. She would have hated the idea of a soundbite, but she had a gift for a capsule phrase, for a story in a word. In their celerity, postcards are the email of the 20th century, but they are also more than that. They tell more than one story: the photographs, paintings and cartoons that Angela chose sometimes reinforce but often contradict the message on the other side. They can contain hidden histories: some of Angela’s images glance back at an episode in her life, or hint at a conversation we had been having. Sometimes, of course, the choice of picture is random: it hints at nothing. In a few years’ time it will be harder to know which is random, which is allusive.

I first looked at these cards when writing a series of talks about postcards for Radio 3; I looked at them again when it was suggested to me that those talks might become a book. I look at them now with the idea that they evoke some of the occasions, preoccupations and delights of Angela’s life. A life of which, as she put it, “The fin has come a little early this siècle.”

Living dolls

Here they are, the girls. Five of them sitting in a row. Some are smaller in girth than others, but all of them have plump curved cheeks, dark almond eyes and slightly open cupid mouths. Each is decorously clad in early 20th-century mode. But their stiff legs are wide apart, their long skirts are partly rolled up; you can see petticoats and a flash of drawers.

The card, posted in the summer of 1989 from London but bought in Hungary, was nearly not sent. Angela’s blue-biro message says: “Budapest is bliss, bliss, bliss. So much so that I never got to post any letters.” She has added in black ink: “I found this among my souvenirs & thought I’d post it off, anyway.” I’m glad she did. Of the cards I’ve seen from Angela, certainly of those she sent me, this brown and white, lush but shadowy photograph is the one that most evokes her stories and essays: not her style – the picture is posed, stately, static, striving for correctness, the very opposite of Angela’s helter-skelter hoopla prose – but her subject matter. These creatures are dolls – it’s hard not to think of The Magic Toyshop – whose bodies are too rigid to be saucy and too adult to be petted; they are showcases of femininity, made-up versions of the sex that makes itself up.

By the time I knew her, Angela’s face was free of make-up and her hair stripped of dye. She was the first woman I knew who went grey without looking like a granny. Her disregard not only for fashion but for neatness was a dirty-strike display. It was not that she was uninterested in people’s appearance – on one of the last afternoons I spent with her she went through our acquaintances ranking them in order of handsomeness. Still, she herself stopped putting on the Ritz. Antonia Fraser, appearing on a television programme with Angela, once said that she had not been able to conceal a flicker of astonishment when Angela had admired her dress. No flicker was ever lost on Angela. “I wonder why people are always so surprised when I’m interested in clothes,” she said, not wondering at all. And laughed.

Angela laughed often and loudly. She was a cackler. She was also a talker, a gasser and a tremendous chatterer on the phone. She knew what it was to make a voice distinctive – as a schoolgirl she had wanted to act – and her own tones were unmistakable.

Piping, soft, with clipped vowels, at times Angela sounded like a parody of girlish gentility. At other times she skidded into casual south London. You never knew exactly where you were. She was impossible to second-guess. She was a great curser, and took pride in this: “I am known in my circle as notoriously foul-mouthed.” Yet she was also byzantinely courteous: her most full-blooded protests would often be heralded by an icily disarming “forgive me”.

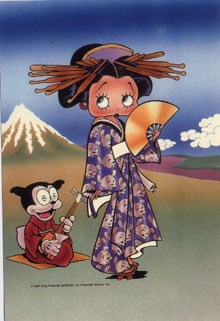

Geisha

Geisha Boop arrived in my flat on a card in vivid Technicolor. The card, evidently sent in an envelope, is undated but must have been dispatched in the late 80s. The message reads: “That was a really terrific party on Monday. I was glad I went. But – why has Marianne gone blonde?!?” It is the reference to Marianne Wiggins that dates the card. The picture itself carries a memory of an earlier time: of Angela’s first big excursion and her escape from England.

In 1969, when she had published three novels and been married to Paul Carter for some eight years, she won the Somerset Maugham award for Several Perceptions. The award, given to a writer under 35, was to be used for travel. Angela fulfilled that requirement, but gave it a twist: “I used the money to run away from my husband, actually. I’m sure Somerset Maugham would have been very pleased.”

She ran to Japan, the only country that met her stringent criteria for a bolthole: she wanted to live in a non-Judaeo-Christian culture, but it had to be a culture with a good sewage and transport system. She had gone off with a Japanese man, a “very good-looking bastard… just what I needed after nine years of marriage”, and it changed her. “I became a feminist when I realised I could have been having all this instead of being married.”

In Japan she became enthusiastic about sex. She found even the ads for the VD clinics jolly: “Let me,” they cajoled, “cure your chronic gonorrhoea.”

Bard

In 1988, four years before she died, Angela sent a Bard card from the Stratford Ontario Shakespeare festival, in Canada. In fluorescent yellow, neo-Renaissance Palatine italics and an exclamation mark, it proclaims: “So I haven’t written much lately! So what? Neither has Shakespeare.”

The message on the back reports only that “Canada’s nice. Especially Montreal. Like Scandinavia with liquor.” At the time she sent this card, Angela was dreaming up Wise Children, her last novel, and her Shakespeare book, a buoyant wise-cracker about hoofing and singing twins. She had set out intending to make in it some reference to all of Shakespeare’s plays: only a few eluded her.

The card may have been offering a semi-apology for a refusal to write something for the London Review; my attempts to coax her on to the page quite often met with refusals. She may have been wincing about the late delivery of a piece of copy. She liked the idea that journalism ran through her veins and was a terrific deadline surfer: “the only time I ever iron the sheets or make meringues is when there is an absolutely urgent deadline in the offing”.

Still, in this Shakespeare card she was most likely nodding to the four years that had passed since the publication of Nights at the Circus. There was a good reason for the gap between Angela’s books. In 1983 she had become pregnant. She was 42, mature for a first-time mother, and she was thrilled and alarmed: “Alex came as a great surprise to us,” she told me. Her pregnancy was not calm. She was not altogether well, and she did not take things easy. One of her tasks was the judging of the Booker prize. It was the year that Fay Weldon presided over an unusually female-strong panel (Angela and Libby Purves sat in judgment alongside the literary editor Terence Kilmartin and the poet Peter Porter), and must have been an unsettling experience for Angela, whose own work had never been selected by a panel of judges.

It was to become even more unsettling. After the dinner at which the announcement of the winner (JM Coetzee’s Life and Times of Michael K) had been made, the television presenter Selina Scott went around with her mic, smiling and making mistakes. She went up to Angela and apparently mistook her for one of the many hangers-on at the feast, inquiring what she thought of the judges’ decision. “I’m one of the judges,” Angela explained, leaning away from her interrogator with a grimly polite chuckle. “Does that exclude me…?” Poor Scott seemed mystified: “I’m sorry… What’s your name?”

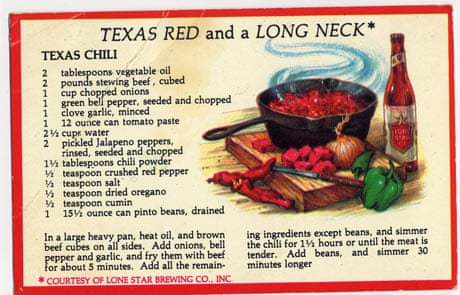

Chili

In 1985 she sent me a postcard from Austin, Texas. The picture showed a black cauldron bubbling with beans and frighteningly red beef, sending off a swirl of blue smoke; alongside it lay peppers, an open bottle of Lone Star beer – and a recipe for Texas Chili. Angela’s message runs: “Carter’s reply to her critics! Texas chili, it goes through you like a dose of salts. I would like to forcefeed it to that drivelling wimp… preferably through his back passage. (I do think all that fuss was comic, though). Temperatures in the ’80s. Everybody is loony, here.”

At the beginning of the year she had reviewed an assortment of volumes about food – The Official Foodie Handbook, Elizabeth David’s An Omelette and a Glass of Wine and the Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook – for the London Review of Books. In a sustained piece of invective, and a dextrous analysis of manners, she tore into “piggery triumphant… [the] unashamed cult of conspicuous gluttony in the advanced industrialised countries, at just the time when Ethiopia is struck by a widely publicised famine”. It was not only the inequity and the waste that enraged her, it was also what she saw as the snobbery of that newly emerging species, the foodie. “This mincing and finicking obsession with food opens up whole new areas of potential social shame. No wonder the British find it irresistible.” Furious responses – some of them alluding to the pregnancy which had delayed her piece – appeared on the paper’s letters pages: “A woman capable of splashing blame for the Ethiopian famine on Elizabeth David is scarcely to be trusted with a baby’s pusher, let alone a stabbing knife.”

These critics were as wrong in thinking Angela uninterested in food as they were in misreading her to mean that foodies were actually responsible for famine. She did take pride in a certain austerity: she spoke of herself as having been formed by the “mild discomfort” of England in the 40s, and approved of its nourishing plainness, of “the fact that you were always a little bit healthily cold, and yet you had brown bread”. Yet austerity in her was the flipside of relish and gusto.

Angela was fiercely interested in the history of food and in its social implications. The book she had chosen for Desert Island Discs was Larousse Gastronomique: she wanted, she said, to take something that would be “a good read”. Still, her interest was also practical, personal. In the kitchen in Clapham she served up rabbit and broccoli, and lamb and apricots (the last cooked with a cat sitting on her lap). She was not much of a drinker; the first time I went to supper at 107 The Chase, I was dashed to see that as soon as the first glasses of white wine had been poured, the bottle was stoppered up and put back into the fridge. She had, she said, cooked “endlessly, elaborately” during her first marriage, and claimed that, after they split up, her husband had accused her of having produced batches of wonderful cakes “in order to make him fat and unattractive to other women. That was characteristic of my Machiavellian mind.”

Angela herself did not eat cakes. Although she was a generous dolloper-out of food, her eating habits had been, for a large part of her life, irregular and sometimes dangerous. As a young girl she had been large, with a chubby face, and had reached her adult height of more than five foot eight by the time she was 13. At the age of 18 she changed shape as dramatically as a creature in one of the fairy tales that fascinated her. She became anorexic.

She was clear about the reasons for this: she wanted to take control of her life and wrest her future away from her parents. Her father was “fearless and unimaginative”, her mother came from “the examination-passing working classes”. Both parents were possessive though in rather different ways; looking back on her adolescence, Angela thought of herself spending a large part of it entrenched in hostility towards them. Her mother indicated that if her daughter got a place at Oxford, she and her husband would be likely to get a flat or house nearby: “I think that’s when I gave up working for my A levels,” Angela explained. And just after she’d taken her exams (only two of them), she gave up eating.

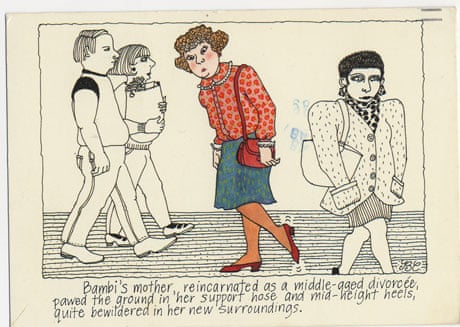

Bambi

“I decided I’d be thin and it all got completely out of hand.” It happened very quickly. She lost about 38 kilos in six months and suddenly looked completely different. She was spindly, with very short curly hair and she did not know whether this extraordinary new appearance was nice or nasty. Sometimes “I looked like Byron”. Often she looked like a model, though even when her shape was tight, her features were luscious. She dressed “like a 30-year-old divorcée”. It was 1958: she got herself up in Chanel-style suits, stilettos and black stockings.

One of her postcards suggests something of this teenage shape-shifting. In the late 1980s Angela sent a droll picture from somewhere near the Erie Canal. It captured her bemusement and her fashion sense, though not the beauty of the young, primly costumed Angela. “I think this is very funny, but I’m not sure why,” runs her message. The caption declares: “Bambi’s mother, reincarnated as a middle-aged divorcée, pawed the ground in her support hose and mid-height heels, quite bewildered in her new surroundings.”

Angela reckoned that as an acute condition her anorexia lasted for about two years, but in its chronic form it went on well into her mature life. Right up to the birth of her son her eating patterns were “still strange”. For some 20 years she levelled out at about 63 kilos but, after Alexander, she steadily put on weight. “But I wasn’t worried any more. I felt so much better when I was fatter. It made me think that inside every thin woman there’s a fat woman trying to get out.”

Ritzy

“Oh,” she said to the artist Corinna Sargood on the phone, soon after the news of her illness had broken, “A man’s coming to the door.” Pause. “It’s all right. I’ll let him in. He hasn’t got a scythe.” In the Brompton hospital a month or so before she died, she worked on the manuscript of The Second Virago Book of Fairy Tales. She had gathered these stories from all over the place – from Norway and Burma and Palestine and Mordvinia – and grouped them under headings which included “Strong Minds and Low Cunning” and “Up to Something – Black Arts and Dirty Tricks”. “I’m just finishing this off for the girls,” she explained, with a nod at the manuscript on her bed.

Back at home, with Mark at the front door warding off people who took it into their heads to drop in, she entertained. I remember her, in October 1991, angry because the Labour Party had rung her on the day she came out of hospital to badger her about a fundraising dinner; she had recently been asked by the Evening Standard why she supported Labour: “Well,” she said, “the Labour Party, it’s like an old sofa, you go on sitting on it even if it is Kinnock-stained.” She was thin, then, and wore a red ribbon wound around her head and tied in a bow.

In the midst of her treatment she concocted a riposte to the Booker, which expressed her comic contempt for much of the fiction flying around the place. Once more missing from the shortlist for the prize, she had, she noted, failed to get the sympathy vote. So she would write a long novel featuring a philosophy don, his mistress and time travelling. It would be called “The Owl of Minerva” – and she knew it would win.

For what turned out to be Salman Rushdie’s last visit, Angela insisted not only on getting up but dressing up, serving tea with an almost Japanese formality, laying out a tea service (perhaps in memory of the rosebud set her mother so cherished) and biscuits. It was one of her gifts to deal in a sort of double irony, to send up a daintiness of manner and yet to honour it at the same time. As she poured, she cursed her illness but took satisfaction from the fact that just before her diagnosis she’d taken out a whopping insurance policy; she “thought it very funny”, Rushdie said, “that the insurance company were screwed”.

The last time I saw her, in January 1992, she was in bed, with light belting in from the windows and the smell of incense, given her by her next-door neighbour, filling the room. We had Tuscan bean soup. She wanted news of parties and literary gossip. She was on steroids and morphine; her face looked rosy and round and smooth. The ribbon in her hair this time was pink, and on the cassette machine at her side she played a tape of Blossom Dearie.

She died on Sunday 16 February. She had had some terrible moments of distress – she told Mark that she had been invaded by aliens – but a large part of her illness had been peaceful, and she had taken command of the organisation of her funeral, leaving precise instructions about who was to be there, what music should be played and what might be read.

On 19 February, at Putney Vale Crematorium, Angela’s brother Hugh played the organ: “Sheep May Safely Graze” at the beginning and ‘”Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” at the end. We sang the 23rd Psalm (“Crimond”). Carmen Callil spoke about her friend. Salman Rushdie read Andrew Marvell’s poem “On a Drop of Dew”. Alexander carried a lily and a red rose to put on his mother’s coffin.

Coming out of the chapel into the hectic luxuriance of the crematorium grounds, it was as if Birnam Wood had come to Putney Vale. The surrounding trees rearranged themselves. They shifted and they sprouted feet. They marched and dispelled, shaking themselves free of foliage. They changed into Special Branch men, who were moving forward to enclose the author of Midnight’s Children, in hiding because of the fatwa imposed on him by the Ayatollah Khomeini three years earlier. The previous year, when Angela was working on the strongly secular television documentary The Holy Family Album, Rushdie had offered her advice on how to deal with blasphemy. “I don’t think,” she had gleefully retorted, “I need any help from you.”

The memorial service, held some five weeks later, was as expansive, inclusive and gaudy as the funeral had been small, plain and sober. Corinna Sargood created a shocking-pink invitation to celebrate Angela’s life and works at the Ritzy cinema in Brixton at 11am on Sunday 29 March. It was Mark who came up with the idea of the Ritzy. It was a homage to Angela’s love of the flicks; the hoofing heroines of her last novel would have felt at home there; it was splendid but battered, and had nothing super or American about it; it was in south London, where she had made her home.

The morning was based on Desert Island Discs. Angela had been asked to go on the programme towards the end of her life: she had chosen her eight records, the book she would take and her luxury, but she was never recorded.

Michael Berkeley, composer, broadcaster and friend, was the compere. He sat on a podium with a cassette machine in front of a folding screen, which Corinna had painted with tropical verdure. He announced the tapes and summoned up the speakers: people from different parts and times of Angela’s life stood in for her voice. Carmen, wearing her koala bear jumper (“for Angie”), spoke, as she had at the funeral. Rebecca Howard talked; so did Caryl Phillips. Tariq Ali fired off about the miners’ strike and made Salman Rushdie cross when he called the Ritzy a fleapit. Lorna Sage arrived just before the morning kicked off: she was pale, slightly stooped and breathless. She, too, was to die in her 50s, but her long blonde hair streamed down as if she were a 19-year-old.

For her records, Angela had chosen Debussy’s “The Girl with the Flaxen Hair”, because Hugh had played it when he was a music student, and Muddy Waters’ “Mannish Boy” because it brought back the 50s. She wanted an extract from Schumann’s Dichterliebe, sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, because it was the first LP she ever bought, and Billie Holiday – her voice shot through with crackles and sighs – singing “Willow Weep”, because it reminded her of Streatham ice rink. She asked for Sviatoslav Richter playing Schubert’s B flat Piano Sonata, which she described as her favourite piece of music; in one of our last meetings she had said she now preferred Schubert to Beethoven – “more heart”. Woody Guthrie’s “Riding in My Car” she chose because she liked being driven and because it reminded her of being in the car with Alexander, who was learning it on his guitar. The penultimate number was Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry” and the final record was one of Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs; Hugh said that was something on which she would never have alighted had she not been ill. In the middle of it, a poster of Wise Children which had been stuck up at one side of the stage came loose and fluttered down.

When the time came for Angela’s luxury to be announced, Mark and Alexander came up from the audience and on to the stage. They turned around Corinna’s bright screen. On the back of the scene of island vegetation she had painted Angela’s choice of luxury. It was a zebra.

Susannah Clapp is the Observer’s theatre critic

A Card From Angela Carter by Susannah Clapp is published by Bloomsbury on 16 February, £10. The book, read by Susannah, will be Radio 4’s Book of the Week from Monday 6 February, 9.45am/12.30am

A conversation with readings from Angela Carter, at The Charleston Trust in 2012

Angela Carter’s vivid literary voice encompassed short stories, novels and essays. The postcards she sent to her friend Susannah Clapp evoke her anarchic intelligence, her fierce politics, the richness of her language, her ribaldry and swoops of the imagination. Susannah Clapp is the theatre critic of The Observer.

Angela Carter’s vivid literary voice encompassed short stories, novels and essays. The postcards she sent to her friend Susannah Clapp evoke her anarchic intelligence, her fierce politics, the richness of her language, her ribaldry and swoops of the imagination. Susannah Clapp is the theatre critic of The Observer.

As an accompaniment to the talk, the actress Hattie Morahan, fresh from her success in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House at the Young Vic, will read one of Angela Carter’s most subversive short stories, The Tiger’s Bride, inspired by Beauty and the Beast.

Chaired by Di Speirs, BBC Radio 4 Editor, Readings.

Click to listen:

Angela Carter has been described as ‘the most consistently interesting and original writer of British fiction today’. Among her most recent books are The Passion of New Eve and The Bloody Chamber. The film The Company of Wolves is based on one of her short stories, and she also co-wrote the screenplay. This interview is taken from a session at Marxism Today’s Left Alive.

Are you conscious of directing the reader to think in a certain way when you write?

It’s very tricky because people are different and people have different responses to fiction. But it’s impossible to direct and I think it wouldn’t be a good thing if you could do it. Reading a book is like re-writing it for yourself. And I think that all fiction should be open-ended. You bring to a novel, anything you read, all your experience of the world. You bring your history and you read it in your own terms. And therefore it’s impossible to quantify what the reaction should be. I went for a long time thinking that perhaps really I should write agitprop, but I couldn’t see how I could. It would come out very odd, it would come out most peculiar. It would come out in such a way that I couldn’t imagine anybody enjoying reading it. And this seemed to cut away, to pull the carpet out from under myself.

If you are writing propaganda you are using the conscious part of your mind to work out what you want to say. Do you do this with fiction? For example, could Countess P in Nights at the Circus be Mrs Thatcher as well as other people – other villains?

Well, of course, she’s not really a character. She’s a proposition. In that story there are two characters. There’s the main character, the woman – Olga. And she’s a proper rounded, three- dimensional character with a history and with a personality, with a lot of low peasant cunning. We know a lot about her. We know a little bit less about the person that she makes contact with. But it’s obvious that it’s a real person even though she’s just hinted at. But the countess – she’s the law, she’s a certain kind of authority. And therefore she doesn’t have to have a character. She doesn’t have to have all this naturalistic apparatus, because all she has to do is sit in the chair and go round and round and round, and be authority. And therefore you can project upon her Mrs Thatcher or the Pope. She can be any authoritarian figure. One of the difficulties of writing fiction that’s supposed to have a lot of meaning and can be read as allegory, is the tension between what people expect from the fiction, which is rounded three-dimensional characters that they can believe in, have empathy with, and the fact that that kind of character doesn’t carry all that much meaning. They can’t carry all that much freight of meaning. They can’t be all that, unless you can try very hard and make them move out of character a lot. It’s a problem that Brecht grappled with, quite successfully.

Do you think fiction that doesn’t have that sort of credibility is also valid?

I’m not sure. I quite enjoy relaxing and writing about people with pimples and ticks because the way that you make a character in ‘straight’ fiction is actually quite simple. You make a sort of checklist of peculiarities. The first editor I ever had said ‘well, say what kind of trousers he’s wearing’. In fact, creating a believable character is something that is quite schematic. There used to be a thriller writer called Peter Cheyney and all the characters in his thrillers were chain-smokers. It took me about three years to work out why this was. It was because ‘he lit a cigarette’, ‘he inhaled thoughtfully’, ‘he stubbed a cigarette out’ – that’s 25 words already and we’re working towards a strict 60,000 words. There’s all kinds of functionalism about mainstream fiction.

Can I ask you a question about your personal life, because I know you’ve just had a baby? How do you organise, how do you make time for work and have you had to redefine yourself as a mother?

It was a year ago. He falls over now. I can’t answer the question because I haven’t actually done very much work since he was born. I keep remembering J G Ballard, who is a single parent, saying how terrific it was that he’s a writer because it meant that he could look after the children as well as earning a living. I keep holding on to that. I keep saying well surely if he can do it, dammit. But in fact really neither me nor my son’s father have done very much work for the last year. I really don’t know how I would have managed if I’d had children when I was young, before I’d established a body of work. I don’t know what kind of a person I would have been, I might have been a much better writer. You can’t guess these things. But certainly organising your life is almost impossible, especially when you’re used to having a certain kind of rhythm of work which has to be completely changed. You only have so much time before it’s necessary to go and pick a small person up. I was forced after 43 years of evasion, to come to terms with my own incompetence. There are lots of things that you can brush under the carpet about yourself until you’re faced with somebody whose needs won’t be put off. You can’t actually tell them to go away and come back in five minutes. I realised that I’m actually an extremely incompetent person and I idle a lot. I’ve got to learn to live with that. But I think I was too old to redefine myself. I couldn’t redefine myself as a mother. I’m proud of my child but I’m not proud of myself as a mother.

Surely you’re wrong. Women much older than you are still redefining themselves everyday of their lives, as women and as people?

I know what you mean. Obviously you change. One changes all the time but I can’t get into the habit of thinking that my being has changed completely just because I’ve done what most women do.

Do you make an effort to write differently when you are bringing male characters into your work?

One of the things that people always say about women writers is that the male characters lack credibility. So when I was a girl I made a conscious effort to make the male characters as credible as I possibly could and to write sometimes in the first person, male. It still didn’t stop people criticising the writing. I suppose I do what I tell writing students: I occasionally get a young man sidling up to me and saying that he was very nervous about writing even the character of a woman, about making female characters, these days, because he thinks that we’re all going to stand around hitting him with our handbags. And I say, this is perfectly correct, ‘yes indeed. This is what will happen to you.’ But what you must do if you want to create a really credible woman is just imagine what you yourself would do in a particular set of circumstances and that’s what she’ll do. Except things like pissing against walls. We tend not to put that in nowadays. One of my students wanted to write about a pregnant woman and I said ‘have you ever felt seasick?’ and he said ‘well, yes’. And I said ‘well, there you go.’ If you start off everyday, except when you were lying down, seasick, you’d start realising what it’s like. Obviously I try and exercise empathy with every person I’m writing about. It’s part of the task to understand things.

I teach on an MA course at the University of East Anglia. The students on it are very highly selected, are extremely highly motivated. Many of them have published quite a lot of work before they come. I see my function to do exactly as a copy editor in a publishing company does: to go through a piece of fiction and say, ‘look he’s wearing odd socks here, what do you precisely mean, here, would so-and-so say such a thing. What are you really trying to get at?’ You have to start out with people who know what they’re doing from the outset.

What about the people who can’t get on a MA course in creative writing, who’ve had a minimal education? It’s going to be a bleak future, isn’t it?

Well, it didn’t matter too much 100 years ago. We were producing very, very much better writers in this country when people were leaving school between twelve and fourteen. I don’t mean to be intemperate but I think this is very important. Reading and living are the real training for writing fiction. This may sound smug but it’s true. What usually happens is that people who actually need to do it will find the time. Often it doesn’t work out. People can put themselves through the most extraordinary privations to write a novel. And then it turns out it’s no good. I’m afraid that’s life. It has happened to me and it was very embarrassing and painful. What I used to do before I wrote a movie and became successful was to organise my life so that I would save up in order to write a novel. I’d put aside money. I’d squirrel it away in building societies. I wrote my first novel in the evenings and at weekends. It was when I was still a student and I did the typing in the summer holiday. As I got better at it, as I became more and more absorbed in the actual work and craft, then it did take me more and more time and I had to do it more and more intensively. It wasn’t possible to do it in a part-time dilettantish, hobbyish sort of way. Then I really did have to start thinking about organising my life in such a way that there would be time to write fiction. I used to do a great deal of journalism to regulate the cash flow. And I’d actually have to clear a lot of that away.

The Company of Wolves and The Bloody Chamber both reveal an extraordinary empathy between human beings and animals.

Well, we are animals, after all. I said this once to somebody after I’d read The Company of Wolves story. She was terribly upset. She said you mean we’re nasty, hairy, dirty slavering beasts. No, no, no, it’s all right. We’re mammals. Bipeds, mammals, carnivorous bipeds, primates and everything. ‘It’s all right’, I said. But she would not be comforted. It was as though a door had opened into hell. I realise I’m sentimental about furred and feathered beings but they’re never dull. I have a minor but quite passionate interest in natural history, I’m a Darwinian. I like animals and I’m interested in animals. I’m also interested in human beings’ projections upon animals of negative qualities, which very often the animals don’t have. Take wolves – the film is a bit less ofa libel on wolves than the story. But the story is an absolute libel on wolves. Wolves in the wild are really quite safe, they don’t mess with human beings unless they’re bothered by them. Their social organisation is somewhat fascistic but who in Britain is to complain about them. I’m interested in the division that Judo- Christianity has made between human nature and animal nature. None of the other great faiths in the world have got quite that division between us and them. None of the others has made this enormous division between birds and beasts who, as Darwin said, would have developed consciences if they’d had the chance, and us. I think it’s one of the scars in Western Europe. I think it’s one of the scars in our culture that we have too high an opinion of ourselves. We align ourselves with the angels instead of the higher primates.

Could we change track a bit and ask where you see yourself in the current debates in the contemporary women’s movement on myths and metaphysics?

I’m quite old-fashioned about this. If you don’t believe in metaphysics, and indeed you don’t approve of metaphysics, then that puts you in a certain position anyway. I’m interested in justice, really. And I think you can do an awful lot more with legislation than people will permit themselves to believe. We seem to be going through a period when the idea that the situation is hopeless has got a certain kind of dark glamour. The idea that one can do nothing seems to be attractive. A lot of people said before the last election that it doesn’t matter whether you vote Labour or Tory. They were capable of saying there’s no difference between them but as far as the details of everyday life are concerned there’s all the difference in the world. I suppose I regard myself as just a rank and file socialist feminist really. That’s all. I worry a lot, obviously. The idea of the soul is a very attractive proposition but nobody has ever been able to prove it to me. I’m very pleased I don’t have religion because all the great religions of the world concur in denying women’s souls and that is such a relief. That is so wonderful.

In The Bloody Chamber you are dealing with fairy tales. Folklore seems to be central to much of your writing?

I’m a great admirer of folklore. Truly, I think the degree to which the bourgeoisie has appropriated the culture of the poor is very interesting, it’s very shocking. Fairy tales are part of the oral tradition of Europe. They were simply the fiction of the poor, the fiction of the illiterate. And they’re very precisely located.

If you mention folklore in Britain, people’s eyes glaze over with boredom. They associate it with people wearing white suits with bells round their legs. It is associated with the embarrassing, with the quaint. Therefore people are genuinely shocked when they look at Grimms’ stories, which the Grimm brothers collected from the German peasants, to see them full of the most ghastly events. One of the stories that I don’t deal with in The Bloody Chamber is about children who are left out in a wood because their parents would rather they starve out of their sight than under their eyes. This, of course, was an everyday fact of most people’s lives in Europe until the industrial revolution. The imagery is perpetually enchanting because a lot of the imagery is the imagery of the unconscious; beautiful and refreshing, it refreshes the imagination. But the circumstances of the stories are simply transformed accounts of ordinary people’s lives. It’s something to do with Western Europe that these stories have gone into the bourgeois nursery and have been dissociated from the mainstream of culture.

Do you think there is anything escapist in your more recent work, especially say The Company of Wolves? Does the success of the film have anything to do with the fact that we are living in a recession?

I would hotly deny that the movie was a piece of escapism. If you gave me five minutes I would be able to construct an absolutely foolproof argument that would convince you that it was about the deep roots of our sexual beings. The Thatcherite censorship certainly found it subtly offensive. They couldn’t put their finger on it but they knew something was wrong. Obviously, depression and recession are great for the entertainment industry and a certain kind of escapist movie is obviously going to be very big at this point in time. I don’t think The Company of Wolves is that kind of film.

Do you feel that in the current political climate it is important that writers are more overt in their politics?

Yes, I suppose I do. There’s a line in a poem of my youth, a poem by Alan Ginsberg called Howl in which he issues this dreadful warning: ‘America, I am putting my queer shoulder to the wheel’. But that sense of weighty responsibility with which some writers approach this fills me with a kind of wild terror. I don’t think art is as important as all that and I don’t think you can do all that much with fiction. It does seem to me that artists, far from being the unconscious legislators of mankind, tend to be parasitic upon those in productive labour. And therefore we really have a big responsibility to deliver the goods. I mean most people would prefer to be artists than to work for Ford in Dagenham after all. Therefore there is a responsibility to deliver the goods, to cheer people up by suggesting that possibly there is hope. I feel that if we all put our queer shoulders to the wheel together, it may be possible to move it an inch, a quarter of an inch, a centimetre, shake it. But it’s very difficult knowing where to start because a certain kind of bland quietism seems to have taken over the intelligentsia.

( by Rosemary Carroll from Bomb — Artists in Conversation)

Angela Carter is a British novelist and short story writer whose works include: The Bloody Chamber , Nights at the Circus and The Magic Toyshop . She also co-wrote the screenplay with Neil Jordan for The Company of Wolves based on her short story of the same title. Ms. Carter’s most recent collection of short fiction, Saints and Strangers was published in September by Viking Penguin. The following interview took place over the phone, late one night in September, between New York and Iowa, where Ms. Carter is teaching at the Iowa Writers Program.

Angela Carter is a British novelist and short story writer whose works include: The Bloody Chamber , Nights at the Circus and The Magic Toyshop . She also co-wrote the screenplay with Neil Jordan for The Company of Wolves based on her short story of the same title. Ms. Carter’s most recent collection of short fiction, Saints and Strangers was published in September by Viking Penguin. The following interview took place over the phone, late one night in September, between New York and Iowa, where Ms. Carter is teaching at the Iowa Writers Program.

Rosemary Carroll How do you like Iowa?

Angela Carter Actually, we like it a lot. This area is uncrowded, with many trees and not much else for miles. This is where the great glacier was held up, right around here, and the land formations are unusual. You can watch a pickup truck drive along an unmade road and see the dust rise from the tires and settle back down. You can’t often do that elsewhere because too many other things happen.

RC I know that you lived in New England for a while, but I presume this is the first time you’ve really spent in the Midwest. Do you find it very different?

AC Yes, it’s quite a surprise. There is so much open space. I hadn’t expected to see so many small rural farms—there’s not much of that left in the United States, is there? It is very low and quiet. We—I and my young man—have a yard here and our son loves it. We watch him turn brown playing in the sun. He has taken to catching crickets and keeping them in a cage. I wonder if there is some rule that people who eat whole foods shouldn’t allow their children to imprison crickets.

RC A vegetarian corollary.

AC Yes, that sort of thing.

RC From reading your books, I had the sense that you have an impression of America as a land that is ultimately somewhat disorienting—a place where the light and the heat are so intense that they are almost crippling or mutating. America comes across as a place where things happen to people and people are not in control, or aware, of their own lives. Is that accurate?

AC I’m not sure. I know what you mean though. I think maybe you’re referring to the short story, The Cabinet of Edgar Allan Poe, the bit about the “laser light of the republic.”

RC Yes, that and The Fall River Axe Murders.

AC Well, they were both written while I was living in Providence, Rhode Island and the area fascinated me. I just walked and watched and listened. (Europeans are often like that around Americans though—like dogs watching their masters.) The atmosphere was so permeated with the Republican virtues. It admitted very little. The feeling was of a place having been chosen and of there being no possibility that the choice was not absolutely correct.

RC And yet in Passion of the New Eve there is this wonderful depiction of the American desert as a place where transformation is easy, almost infinitely possible, even if it’s not a desirable transformation.

AC I think the transformation in the novel was certainly desirable. I have actually seen the desert here, though. I made the great cross-country trip Americans always say they want to make. In 1969 my husband, my first husband, and I drove across the United States in a Greyhound bus. We went from New York to San Francisco, by way of New Orleans because we were both fond of the jazz music from there. We went south to El Paso and then through the desert to California. The whole trip only lasted six days but it was quite an experience.

RC I have been wanting to ask you whether you liked Neil Jordan’s film version of your story The Company of Wolves?

AC Well, I wrote the script, you know.

RC You and he collaborated on the script, didn’t you? I imagine the collaborative process would be very difficult. It reminds me of something William Burroughs once said to the effect that to collaborate is to lie.

AC Oh no, we got along very well. We are good friends and I enjoyed doing it. I’m just sorry for Neil’s sake that the movie didn’t do better commercially. I was afraid that would really hurt his chance to make future films. But his new movie, Mona Lisa, is doing very well, so he’s hitting the high spots.

RC But the end of the film Company of Wolves is so different from the story.

AC I was furious about the ending. It wasn’t scripted that way at all. I was out of the country—in Australia when he shot the ending and he told me that it varied somewhat from the script. When I went to the screening I sat with Neil and I was enjoying the film very much and thinking that it had turned out so well—just as I had hoped. Until the ending which I couldn’t believe—I was so upset, I said, “You’ve ruined it.” He was apologetic.

RC How had the ending originally been scripted?

AC After she encounters the wolf at her grandmother’s house and what has happened becomes apparent she wakes up. Her body elongates beautifully and she does a perfect swan dive into the floorboards which turn into the surface of a body of water that swallows her. But that proved impossible to film. They tried covering the floor with water, but that didn’t work and she couldn’t just dive into the floor.

But even if it wasn’t possible to end the film as planned, I wish he had ended it right after the part where the white rose turns red.

RC I prefer the way your story ends—with her lying in grandmother’s bed between the wolf’s paws.

AC I do, too. Neil kept trying to convince me that his ending was potentially more ambiguous than it seemed. He maintains that her screams when the camera is panning the outside of the house are screams of pleasure, but it certainly doesn’t seem that way to me.

RC I think men frequently have the mistaken belief that women are screaming in pleasure rather than in terror.

AC True. Perhaps the problem is that Sarah Peterson is not a very explicit screamer. In any case, I really did like the movie as a whole. I try to think that the falsity of the ending won’t even be noticed—everybody in the audience will be looking for their shoes and it will go right by.

RC I read an interview with Neil Jordan recently in which he asked what prompted his transition from writing fiction to making films. He said it was related to an increasing awareness on his part of the extent to which his prose had always been affected by cinema. He became more and more obsessed with the look and shape of things and began to feel that prose was an inadequate method of conveying these concerns. Is that a feeling you share? Do you have any desire to do more writing for film?

AC I enjoyed working on Company of Wolves with Neil. And I have done some other work on scripts. When I do it I like it but I have no great desire to seek it out. Right now, Granada Television is making a film based on another work of mine, my second novel, The Magic Toyshop. I’m quite pleased with it actually. It will be a television movie, at least initially, and so, of course, the budget is much lower than it was for Company of Wolves. The cast includes this wonderful English actor, Tom Bell, have you ever heard of him?

RC No, is he going to play Finn?

AC No. He is cast as the uncle. He specializes in heavies—gangsters, Nazis and so on. He has a fantastic knack for portraying motiveless malignity, he will be just right. The director, David Wheatley, has worked mostly for British television—what drew us together was a film he made ages ago about the Brothers Grimm, that was full of terrific imagery and invention. David started out as a sculptor, oddly enough. We had a lovely time inventing imagery for The Magic Toyshop. He has a real feel for the book.

RC I love that book—it is such a stunning evocation of adolescence. The scene in which Melanie is trapped while climbing the tree in her mother’s wedding gown is perfect—it completely captures that feeling of uncertain anticipation. This is an underconnectedness of events and you don’t know which one is dependent on the other but you know that there is an incredibly important relation between them and it is all very wonderful and frightening at the same time.

AC You liked that? I’m glad. I am hopeful about the movie. I don’t think it will suffer from the small budget, because that story shouldn’t really require so much money to realize on film.

RC I think that is true. Besides, a lower budget doesn’t always translate into a good movie; in fact, the inverse is sometimes true. Do you feel that your prose is affected by cinema?

AC Since I’ve become a mother, I don’t go to the movies much. But certainly the way I view the world has been influenced by them. I think that must be true for most writers. The early Godard films had a very strong effect on the way I observe and see the world. They are extraordinary. And not just Godard. For example, I think of Barbara Stanwyck’s descent down the stairs in Double Indemnity. First, you see the stiletto-heeled shoe then the ankle with the chain around it, then the legs and the full, rich shine of her stockings. You know she is going to be a femme fatale long before you even see her face.

RC Have you seen Hail Mary?

AC No, I refuse to. I could hardly believe Godard would do such a thing. I’ve read about it and I saw clips from it on television and all I could think of was “Jean Luc, you have crapped upon an entire generation.”

RC What is your favorite movie?

AC You mean my favorite movie ever, of all time.

RC Yes.

AC I would have to say that it is Marcel Carne’s Les Enfants du Paradis, with a script by Jacques Prévert and extraordinary performances by just about everyone who was anybody in the French cinema: Jean-Louis Barrault, Arletty, Maria Cesarés . . . It is the definitive film about romanticism; and about the impossibility of happy endings; and also about the nature of monochrome photography, and the character of Pierrot in the Comedia del Arte and lots of things. It is an enormous, cumbersome, comprehensive world of a movie, and one in which it always seems possible to me, I might be able to jump through the screen into, and live there, in a state of luminous anguish, just like everybody else in the movie.

RC Much of your work seems to exist in the borderline area between consciousness and dreams. The stories are dreamlike in structure and share other qualities with dreams—symbolic transformations, ritualistic, referent use of name and language, and the fulfillment of unexpressed, or even denied, desire. Do you keep a journal of your dreams?

AC I don’t dream. Rather, I never remember my dreams and on the rare occasions when I do, they are completely banal. Last night, for example, I dreamed that I woke up and went to the bathroom.

But this resemblance to dreams is deliberate, conscious as it were. I have studied dreams extensively and I know about their structure and symbolism. I think dreams are a way of the mind telling itself stories. I use free association and dream imagery when I write. I like to think I have a hot line to my subconscious.

RC One of the themes that recurs is concerned with a sort of cataclysmic upheaval in childhood. Were you uprooted when you were a child?

AC All English children in my generation were, at least all those living in London. I was born in 1940. My mother left London carrying me in her arms with my 12-year-old brother. Almost no one remained actually living in London at that time. We went south to Sussex and stayed there for a while. Then we went to live with my grandmother in the country in the North. My mother would stay with my grandmother and I for a few weeks and then commute to London to be with my father and then return to us. But I remember this as a happy time somehow.

RC That is interesting to me—that you grew up essentially as an only child in a house full of women. The aspect of your work that I most appreciate is this unique sense of real love for, and protectiveness towards, other women. It is something that I look for in women writers and almost never find.

AC What you say about the feeling toward women makes me happy—because it is very important to me. But I don’t understand your comparison to other women writers. What do you mean?

RC Women writers frequently adopt a tone or an attitude toward their female characters which is somewhat negative and ungenerous. It comes across as either whining self-indulgence or congratulatory, stolid self-reliance. There is so little compassion.

AC To whom do you refer?

RC Let’s say, Joan Didion, for example.

AC Yah, boo, sucks. Although I am a card-carrying and committed feminist, what I would like to see happen to Joan Didion’s female characters is that a particularly hairy and repulsive chapter of Hells Angels descend upon their therapy group with a squeal of brakes and sweep these anorexic nutters behind them despite their squeaks of protest. Like a version, dare I say it, of the rape of the Sabine women. And bear them off to hard labour in the grease pits. Or else ten years compulsory re-education in the coffee plantations of Nicaragua might do the trick, make those girls feel there are worse things in life than running out of valium. Except what lousy fun it would be for the Angels. And the Nicaraguans might feel with justice it was a particularly foul CIA plot.

Actually, I think Joan Didion is an alien from another planet. Can we talk about a real novelist?

RC To take a somewhat less obviously despicable example, then—Doris Lessing.

AC She is quite an odd one, too. But as far as her feelings toward women or women characters go, they don’t seem objectionable.

RC She seems incapable of finding sustenance or delight in the company of women. There is such an absence of joy.

AC I wouldn’t limit it to her women characters, though. Some people think life is worth living and others really don’t see the point of the whole thing. She is one of the latter—it is her entire view of the world,

RC The only woman I can think of, off hand, who is different in this respect is Jane Bowles.

AC Now you’re talking. She is wonderful, extraordinary. But what a tragically sad end she met—it is, I suppose, a particularly poignant example of the terrifying fatality of being a woman.

RC In the Sadeian Woman you stated that in Sade’s work women do not exist as a class and are subsumed into the general class of the weak, the tyrannized, and the exploited. There is a suggestion that this denigration is connected with the fact that the reproductive aspect of female sexuality was completely devalued in Sade’s culture. Assuming that is valid, its antithesis leaves us with the earth-mother-goddess as the essence of the “valued” woman. And that is a somewhat problematic role model for women in the 20th century.

AC Or any century for that matter. Societies have never placed a very high value on the reproductive capacity of their women. The productivity of land, the availability of natural resources, the fecundity of thought, these are the things that must be valued.

What concerns me is the fact that the actual physical aspect of this has been ignored for so long. Statistics are compiled about infant mortality. What about maternal mortality? I have three close friends who have had children within the past several years for whom successful childbirth would have been impossible five years ago. All of them would surely have died. I have been reading a collection of Chinese short stories written in China in the 1920s. The only woman writer in the collection died in childbirth at the age of 34. And in so many parts of the world this situation is still unchanged. The reality of it is ignored, or not focused on. Women have not had a voice until so recently and even now this issue is not one with which the women’s movement seems concerned.

RC Had you always wanted to have a child?

AC No, never. They had to drag me, kicking and screaming, into the labor ward. I kept insisting that it was too late, that I was too old for such things.

RC Has being a mother changed your perspectives?

AC No, not really. Well, it has changed my life. We have so much less time than we did. His father’s life is just as changed as mine.

But Alexander, my son, is a wonderful little person. He is going on three. I am getting used to having these great numbers of people in the car that are all his friends, his made-up friends. He is amazingly busy all the time, and that is hard work.

But we both feel the impact and the joy and the strain. I don’t think that Alexander has a greater effect on me necessarily. That is part of the myth of sexual difference.

RC What is the myth of sexual difference?

AC The idea that maleness is normative and that women’s difference from men is somehow pathological. This mythology lends itself, for example, to the idea that there is some mysterious connection between women and madness when in fact women are no more specifically connected with madness than are men.

RC I wanted to ask you about mythology in general and its place in your work. Reviewers and critics frequently stress the presence of mythological and fabulist elements in your fiction. Yet, you have said, “Myths deal in false universals to dull the pain of particular circumstances.” Do you think this critical emphasis is misplaced?

AC Yes, but I understand how it’s happened—there is something classy about invoking myth, it implies you’ve got a college education, people like to spot myths, it makes them feel good. That’s fine. I am interested in the way people make sense, or try to make sense, of their experience and mythology is part of that, after all. I’m a Freudian, in that sense, and some others, too. But I see my business, the nature of my work, as taking apart mythologies, in order to find out what basic, human stuff they are made of in the first place.

—Rosemary Carroll practices entertainment law in New York City and is a regular contributor to BOMB.

By Anna Katsavos

(From “The Review of Contemporary Fiction,” Fall 1994, Vol. 14.3)

Crammed in with all the other gear packed for a ski trip was my copy of Angela Carter’s newest novel, Wise Children. Because sheer exhaustion made it difficult for me to stay awake past nine o’clock, I didn’t get to finish the book, which in a sad kind of way turned out to be a good thing.

A week later I returned home to a stack of unread newspapers and very sorrowful news; while I had been struggling with moguls, Carter had succumbed to cancer. Though my dealings with her were limited (a few letters, phone calls, and two personal meetings), the sense of loss that I experienced was deep-felt. I immediately went for my copy of Wise Children, and for a long time gazed at the picture of the author’s smiling face on the inside jacket; it was the same picture as the one in the Times’s obit. Mixed in with my numbness was a peculiar sense of gratitude that there was something new she could say to me still. I began to read, but my thoughts kept reverting to that crisp November morning in 1988 when I had the pleasure of chatting with this woman over breakfast.

We met in the lobby of a well-known New York hotel, where she introduced me to Alexander, her son, who was off with his father to spend a few hours sightseeing in the big city. (Their arrangements—to meet at noon by the big clock in front of F.A.O. Schwarz—made me chuckle; recalling the clocks, magic, and toys in Carter’s fiction, I thought that New York’s own magic toyshop was, of course, the most fitting place to meet.)

My interview with Angela, as she insisted I call her, was to my surprise like visiting with an old friend. We talked about our young sons; we sized up the company around us; and we made one sexually loaded comment after another, each of us trying, like comedians in the spotlight, to get the last laugh. Not surprisingly, she won, hands down. I was having so much fun that I nearly abandoned the interview questions that Angela so graciously and patiently answered before we parted. We hugged, I thanked her, and she urged me to write to her if I had additional questions; I did, indeed, but many of them will remain unanswered.

ANNA KATSAVOS: In “Notes From the Front Line” you say that you are not in the remythologizing business but in the “demythologizing business.” What exactly do you mean?

ANGELA CARTER: Well, I’m basically trying to find out what certain configurations of imagery in our society, in our culture, really stand for, what they mean, underneath the kind of semireligious coating that makes people not particularly want to interfere with them.

AK: In what sense are you defining myth?

AC: In a sort of conventional sense; also in the sense that Roland Barthes uses it in Mythologies—ideas, images, stories that we tend to take on trust without thinking what they really mean, without trying to work out what, for example, the stories of the New Testament are really about.

AK: In modern poetry women openly use traditional figures of patriarchal mythology, figures like Circe, Leda, Helen, not only to reinvent them but to retell their stories, as you say in The Sadeian Woman, “in the service of women.” To what extent do you rely on traditional mythical figures in your writing? Are you drawn more to a particular mythology than to another?

AC: I used to be more interested in it. I’m not generally interested in doing that. I mean I’m not terribly interested in these particular characters. The second novel that I wrote, a very long time ago, The Magic Toyshop, has a whole apparatus about Leda and the swan, and it turns out that the swan is just a puppet. I wrote that a very long time ago, when I really didn’t know what I was doing, and even so it turns out that the swan is an artificial construct, a puppet, and, somebody, a man, is putting strings on the puppet. That was ages ago, over ten years ago, when I wrote that. The idea was in my mind before I had sorted it out. But I just stopped using these configurations because they just stopped being useful to me.

AK: And yet in Heroes and Villains myths are not seen as extraordinary lies designed to make people unfree but rather as something necessary and useful. Donnaly promises to make Jewel a politician, king of all the Yahoos and all the Professors, saying, “they need a myth as passionately as anyone else; they need a hero.”

AC: When most people are writing over a period of years, what they think they are writing about and what they believe in is a continuum; it’s not “specktic.” I’ve been publishing fiction since 1966, and I’ve changed a lot in the way I approach the world and in the way that I organize the world.

Heroes and Villains was quite an important book for me. One of the quotations in the front is from the script of a film called Alphaville, made by Jean-Luc Godard. It was a favorite film of mine of the late sixties; there’s a computer in Alphaville that says the thing that’s quoted in the front. [“There are times when reality becomes too complex for Oral Communication. But Legend gives it a form by which it pervades the whole world.”] In these times myth gives history shape. When I wrote that novel in 1968, this was a very resonant theme that I am not so sure of now.

I think that Godard was using the word myth in the same way that Barthes is as well. The film Alphaville uses one of the greatest gangster heroes of French cinema, but it projects a sort of trench-coat, Philip Marlowe character into some sort of antiseptic city of the future, and I really think that he was meaning myth in the terms of somebody like Bogart or Philip Marlowe. You know, you try things out and you try things out, and you figure out after a while when they’re not working or they stop working or maybe you no longer think it’s true. I just became uninterested in these sort of semi-sacrilized ways of looking at the world. They didn’t seem to me to be any help.

AK: What about Fevvers in Nights at the Circus? Would you say she’s out to create her own myth?

AC: No, Fevvers is out to earn a living. Everything she says in that direction is undercut by her mother, but the stuff that she says in the beginning about being hatched from an egg, that’s what she says. We are talking about fiction here, and I have no idea whether that’s true or not. That’s just what she says, a story that’s being constructed. That’s just the story of her life. Part of the point of the novel is that you are kept uncertain. The reader is more or less kept uncertain until quite a long way through. When she is talking about being a new woman and having invented herself, her foster mother keeps on saying it’s not going to be as simple as that. Also, they have quite a long conversation about this when they are walking through the tundra.

One of the original ideas behind the creation of that character was a piece of writing by Guilliaume Apollinaire, in which he talks about Sade’s Juliette. He’s talking about a woman in the early twentieth century, in a very French and rhetorical manner. He’s talking about the new woman, and the very phrase he uses is, “who will have wings and will renew the world.” And I read this, and like a lot of women, when you read this kind of thing, you get this real “bulge” and think, “How wonderful…How terrific,” and then I thought, “Well no; it’s not going to be as easy as that.” And I also thought, “Really, how very, very inconvenient it would be for a person to have real wings, just how really difficult.”

Fevvers is a very literal creation. She’s very literally a winged spirit. She’s very literally the winged victory, but very, very literally so. How inconvenient to have wings, and by extension, how very, very difficult to be born so out of key with the world. Something that women know all about is how very difficult it is to enter an old game. What you have to do is to change the rules and make a new game, and that’s really what she’s about.

That novel is set at exactly the moment in European history when things began to change. It’s set at that time quite deliberately, and she’s the new woman. All the women who have been in the first brothel with her end up doing these “new women” jobs, like becoming hotel managers and running typing agencies, and so on, very much like characters in Shaw. There’s a Barrie play called The Twelve-Pound Look, about a woman who spends twelve pounds on a typewriter, and she gets that twelve-pound look in her eyes because she can now have everything…. By the time I wrote The Sadeian Woman, I was getting really ratty with the whole idea of myth. I was getting quite ratty with the sort of appeals by some of the women’s movements to have these sort of “Ur-religions” because it didn’t seem to me at all to the point. The point seemed to be the here and now, what we should do now. And that is when I started getting ratty about it.

AK: What is your definition of speculative fiction, and do you consider yourself part of such a tradition?

AC: Well, I have had some following in science fiction. I didn’t read a lot of science fiction when I was younger, but there was a whole group of science fiction writers in Britain in the sixties, who really were doing very extraordinary things with the genre. They weren’t writing about bug-eyed monsters and space at all. One of them, J. G. Ballard, coined this phrase, “inner space.” I was quite profoundly affected by them. They are all still working, and Ballard is, I suppose, the most important. Michael Moorcock has written more books than anyone else in the history of the world, two shelves. It seemed to me, after reading these writers a lot, that they were writing about ideas, and that was basically what I was trying to do.

Speculative fiction really means that, the fiction of speculation, the fiction of asking “what if?” It’s a system of continuing inquiry. In a way all fiction starts off with “what if,” but some “what ifs” are more specific. One kind of novel starts off with “What if I found out that my mother has an affair with a man that I thought was my uncle?” That’s presupposing a different kind of novel from the one that starts off with “What if I found out my boyfriend had just changed sex?” If you read the New York Times Book Review a lot, you soon come to the conclusion that our culture takes more seriously the first kind of fiction, which is a shame in some ways. By the second “what if’ you would actually end up asking much more penetrating questions. If you were half way good at writing fiction, you’d end up asking yourself and asking the reader actually much more complicated questions about what we expect from human relationships and what we expect from gender.

AK: Are you moving towards stories that are less elaborately speculative?

AC: Yes, I suppose so. The stories in The Bloody Chamber are very firmly grounded in the Indo-European popular tradition, even in the way they look. A friend of mine has just done a collection of literary fairy tales from seventeenth-and eighteenth-century France, things like the original “Beauty and the Beast,” which is in fact from the oral tradition. There’s this long history in Europe of taking elements from the oral tradition and making them into very elaborate literary conventions, but all the elements in that particular piece, The Bloody Chamber, are very lush.

I was looking at it again last week. I read from it for the first time in ages the other night, and I thought, this is pretty cholesterol-rich because of the fact that they all take place in invented landscapes. Some of the landscapes are reinvented ones. “The Bloody Chamber” story itself is set quite firmly in the Mont Saint Michel, which is this castle on an island off the coast of Brittany; and a lot of the most exotic landscapes in it, the Italian landscapes, were quite legit. “The Tiger’s Bride” landscape, admittedly, is touristic, but it’s one of the palaces in Mantua that has the most wonderful jewels, and that city is set in the Po Valley, which is very flat and very far out, so in the summer you can imagine the mist rolling over. The landscapes there [The Bloody Chamber] are quite real. Even the werewolf stories are set in some horror-filled invented landscapes, but there’s more a kind of down-to-earthness in those stories.

AK: Isn’t that what makes them work?

AC: Sure.

AK: At the reading you gave in October 1988 at the Graduate School and University Center of the City University of New York, you spoke about the private pleasure of writing, of playing games with the reader. What sort of games do you most enjoy playing with your reader?

AC: You probably noticed a lot of them. I’m doing it less, actually, because I have less time. I’ve noticed a very definite shift in my works, a most definite shift. Although sometimes when I read the stories that I wrote a long time ago, I think, “Oh goodness, how could I have thought of that?” I find myself thinking much more simply because I’m spending so much time with a small child. [At the time of the interview, Carter’s son was five.]

I was reading “The Company of Wolves” the other day, and there are a whole lot of verbal games in that that I really enjoy doing, “the deer departed,” for example. People very rarely notice these when I’m reading them, but I think if you read it on the page. There was one thing in the movie The Company of Wolves, when the werewolf-husband says he’s just going out to answer a call of nature, and one of the critics wrote to me and said, “I didn’t even notice this the first time.” That’s the sort of thing I like doing. These are sort of private jokes with myself and with whoever notices, and I used to enjoy doing that very much. There are lots of them in Nights at the Circus, which was intended as a comic novel.

I’ve always thought that my stories were quite loaded with jokes, but the first story that I wrote that was supposed to be really funny, out and out funny, was a “Puss-in-Boots” story in The Bloody Chamber. I mailed that to a radio place, and they censored it. (It was done on what we call Radio Three, an art channel, which uses a lot of material from BBC Radio and World Service that you don’t get here.) They cut it! They removed, according to the producer, about half a spool of bed springs!

AK: In the afterword to your short story collection Fireworks you write that “the limited trajectory of the short narrative concentrates its meaning. Sign and sense can fuse to an extent impossible to achieve among the multiplying ambiguities of an extended narrative.” Do you see yourself staying in this genre?