(from The Invention of Angela Carter by Edmund Gordon)

Angela Carter and her husband, Paul, flew to New York on July 29, 1969. They arrived in the aftermath of the Stonewall riots, when the city was fractious and twitchy in the midsummer heat. A few weeks earlier, the first American troops had withdrawn from Vietnam (an outcome Angela thought was “in human terms … the single most glorious event since the abolition of slavery”), but in August the headlines were dominated by gun battles between Black Panthers and police, the bombing of the Marine Midland building on Broadway by a radical left-wing activist, and the gruesome murders perpetrated by the Manson family in Los Angeles and the Zodiac Killer in San Francisco. Angela felt that the status quo “couldn’t hold on much longer. The war had been brought home.” She found Manhattan “a very, very strange and disturbing and unpleasant and violent and terrifying place … The number of people who offered to do me violence was extraordinary.” The trip was the basis for the Expressionist portrait of New York in her novel The Passion of New Eve—it’s depicted as a society in the last stages of moral and economic collapse—which she described as “only a very slightly exaggerated picture, not of how it was in New York but of how it felt that summer.” She met one of the models for Tristessa—the novel’s transvestite leading lady—in Max’s Kansas City, the legendary nightclub in the East Village where the house band was the Velvet Underground,and the clientele was composed largely of artists, writers and musicians, including such luminaries as Andy Warhol, William Burroughs, and Patti Smith.

Angela and Paul spent three days in the city before traveling by Greyhound bus through Connecticut, Maryland, Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Angela wrote to her friend Carole Roffe:

Riding the buses is weird, since one sees only the Other America—the poor people, spades, Mexies, mountain men & European tourists. Everyone else is in a car or plane. Eating at bus station cafes in strange dawns, each station identifiable only by the differing postcards in the stand & the sugar lollipops labelled A Present from Knoxville … Or Phoenix or Memphis depending on the town. Black girls twisting their hair into spikes & applying the de-kinking fluid as the bus roars at 70mph through a Mississippi night, a fanfare of electrographics heralds another city.

The rush of the prose suggests something of the disorientation produced by visiting eleven states in just over a month. She hardly had time to process her impressions of one before moving on to the next. In New England, they spent a few nights sleeping in a log cabin in a redwood forest. In Virginia, they stayed with a Scottish weaver who “brewed Typhoo tea while nibbling imported shortbread & sighing for black pudding as though it were the fruits of a lost Eden”. In Arizona (“the most beautiful, barren, wild place”), they passed a Comanche village, and through the bus window Angela watched a young boy throwing stones at a wasted Chevrolet—“the only glimpse I caught in all my travels in America of the vanishing American himself.” On the Berkeley campus of the University of California, “saffron-robed figures sang and danced ‘Hare Krishna,’ to my exquisite embarrassment, and everywhere they advertised burgers—hamburgers, bullburgers, broilerburgers, every kind of burger including Murphy’s Irish Shamrockburger.” She thought that America was “like a Godard movie, like all the Godard movies playing at once,” but also “a nation entirely without voluptuousness.” It was an ambivalence that stayed with her, though she returned to the country several times. At the very end of her life—having lived for periods in Texas, Iowa, Rhode Island, and New York State—she wrote: “I think of the United States with awe and sadness, that the country has never, ever quite reneged on the beautiful promise inscribed on the Statue of Liberty … and yet has fucked so much up.”

The only constant was her traveling companion. But Paul isn’t mentioned in either of the short pieces of journalism she wrote about the trip (for BBC Radio 3 and the Author), or in the journal entries she made while they were there, or even in her letters to Carole. It’s an eloquent omission, as her later descriptions of the journey make clear. The narrator of “The Quilt Maker” recalls traveling by bus around the USA, “somewhere along my thirtieth year,” in the company of “a man who was then my husband.” At the bus station in Houston, Texas, she asks him for money (“he used to carry about all our money for us because he did not trust me with it”) to buy a peach from a vending machine. There are two peaches available in separate compartments of the machine, and she selects the smaller one; he teases her about this instinctive self-denial. “If the man who was then my husband had not told me I was a fool to take the little peach,” she says, “then I would never have left him, for in truth, he was, in a manner of speaking, always the little peach to me.”

Even so, she hadn’t finally decided on leaving Paul when, on September 3, they boarded separate flights at San Francisco Airport. It’s clear from subsequent letters that they parted on good terms: there had been no dramatic bust-up, and the plan was still for her to return to Bristol in late October. Neither of them imagined that it would be their last moment together as a married couple.

►

Explore 3D Space

►

Explore 3D Space

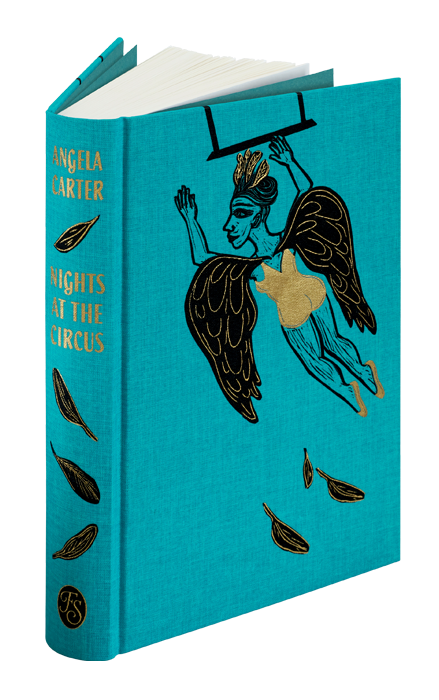

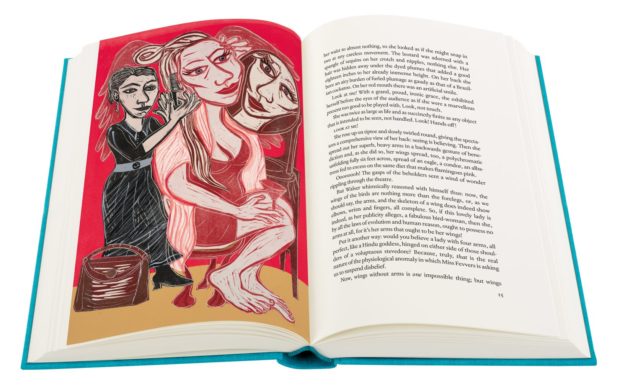

The Folio Society are issuing a lavish, illustrated edition of Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, with dazzling artwork by Eileen Cooper of the Royal Academy – you can read an

The Folio Society are issuing a lavish, illustrated edition of Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, with dazzling artwork by Eileen Cooper of the Royal Academy – you can read an

Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber is ranked number 25 in

Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber is ranked number 25 in