Novelist Angela Carter’s surprising take on a notorious writer

(from Scroll.in)

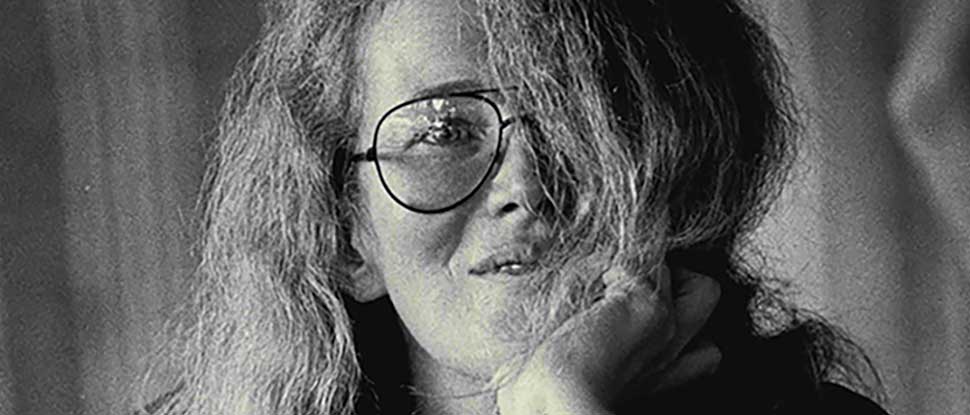

Social constructs and questions of control are preoccupations the late British writer Angela Carter returns to time and time again. This is especially true of the inflammatory piece of feminist non-fiction Carter published in 1979: The Sadeian Woman: And the Ideology of Pornography.

Carter, who died from cancer in 1992, was a true creative trailblazer. A novelist, fabulist, journalist and editor, deeply influenced by the women’s movement of the 1960s, she played with genres from fairy tales and science fiction to magic realism and radio drama. She is known for works such as The Bloody Chamber (1979) and Wise Children (1991).

Her work is eerily prescient and continues to resonate. The Passion of New Eve (1977), for instance, is a transgressive feminist novel set in a post-apocalyptic United States. Tellingly, Carter described this novel as an “anti-mythic” work about “the social creation of femininity”.

Two years later, she published her take on the French writer the Marquis de Sade (1740-1814). Commissioned by the feminist publishing house, Virago, The Sadeian Woman attempts the near impossible, claiming Sade as a proto-feminist author.

Fact from fiction

Novelist Francine du Plessix Gray has described Sade (whose real name was Donatien Alphonse François) as “one of the few men in history whose names have spawned adjectives” and “the only writer who will never lose his capacity to shock us.”

But who was he? Carter’s introductory note to The Sadeian Woman is useful:

Sade was born in 1740, a great nobleman; and died in 1814, in a lunatic asylum, a poor man. His life spans the entire period of the French Revolution and he died in the same year that Napoleon abdicated and the monarchy was restored to France. He stands on the threshold of the modern period, looking both backward and forwards, at a time when the nature of human nature and of social institutions was debated as freely as it is in our own.

Yet Carter neglects to mention Sade is one of the most notorious writers in recorded history.

Insane pornographer. Sexual pervert. Woman beater. Child rapist. Murderer. As the professor of French literature John Phillips has observed, these are “some of the more lurid labels” that have been attached – sometimes erroneously – to Sade over the last two centuries.

Sade is the author of 120 Days of Sodom amongst other works, a novel so repellent that, in the words of the philosopher and pornographer George Bataille, one cannot finish it “without feeling sick”. Two of Sade’s other major novels were Justine, or, The Misfortunes of Virtue (which describes the sexual brutalising of a 12-year-old virgin) and Juliette, or, The Prosperities of Vice, chronicling the adventures of Justine’s libertine older sister.

The shocking nature of Sade’s writing causes problems, especially because readers have difficulty distinguishing fact from fiction when it comes to him.

Sade was responsible for unquestionably abhorrent criminal behaviour in his personal life, such as when he kidnapped and abused Rose Keller, a 36-year-old beggar woman. He was found guilty of rape, sodomy and torture in the case of Keller. Once released, he went on to commit a series of other crimes. For these offences, Sade spent decades in prisons or insane asylums.

Sade started writing while incarcerated. His brutally deterministic fictional universe is one where, in his own words,

it is essential that the unfortunate should suffer. Their humiliation and their pain are numbered among the laws of Nature, and their existence is essential to her overall plan, as is that of the prosperity that crushes them.

Unpalatable as this may be, it is hard to ignore Sade. He has inspired artists and thinkers such as writers Gustave Flaubert, André Breton and Michel Foucault, film-maker Pier Paolo Pasolini and the feminist philosopher Simone du Beauvoir. The latter reasoned

Sade drained to the dregs the moment of selfishness, injustice, misery, and he insisted upon its truth. The supreme value of his testimony lies in its ability to disturb us. It forces us to re-examine thoroughly the basic problem which haunts our age in different forms: the true relation between man and man.

Angela Carter, who knew her Beauvoir, advances a similar argument in The Sadiean Woman. Carter’s interest in Sade dates back to the beginning of the 1970s, when she contemplated writing a PhD entitled “De Sade: Culmination of the Enlightenment”. (read the full article here)

I

I

►

Explore 3D Space

►

Explore 3D Space

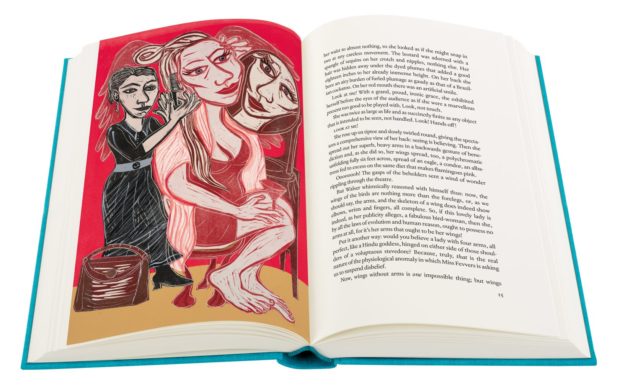

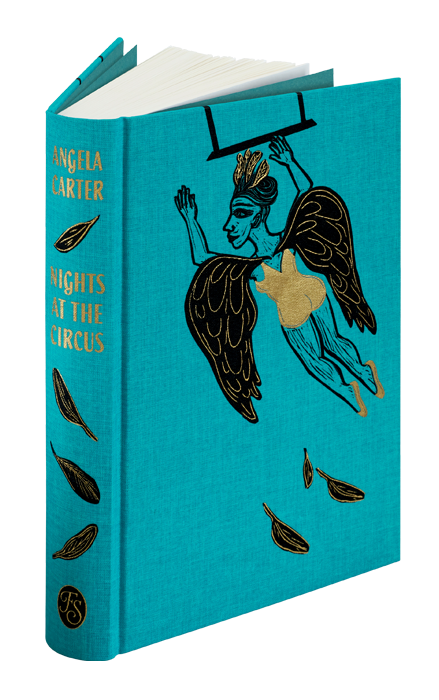

The Folio Society are issuing a lavish, illustrated edition of Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, with dazzling artwork by Eileen Cooper of the Royal Academy – you can read an

The Folio Society are issuing a lavish, illustrated edition of Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus, with dazzling artwork by Eileen Cooper of the Royal Academy – you can read an